It’s a rare opportunity – if you have it now – to step back and evaluate yourself and what you want. So many reasons prompt us to take a look in the mirror. Questions such as “Is this really what I want to be doing?” “Is this the best use of my time and talent?” “Does this work really sync with my values and purpose?”

Instead of rethinking the job, rethink yourself. Jumpstart clear thinking with this handful of “classic” questions.

I have always believed the formula for strategic thinking and planning at the group or organizational level applies equally to personal strategic thinking and planning. Just as you might do an external scan of the environment in which you operate, an internal scan of your self – your strengths, conditions in which you do your best work, the contribution(s) you want to make over the coming 12 to 18 months.

Our success relies on how well we know and manage ourselves. Commitment to our personal and professional development helps steer us on our path toward the places we can make the greatest contribution and reap the greatest satisfaction.

It also feeds our ability to know when it’s time to change what we do.

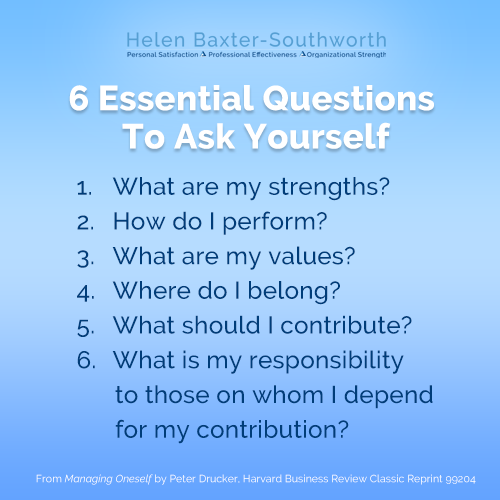

Here are “classic” questions from management – and “self-management” thinker Peter Drucker. Drucker relied on the habit of answering a handful of questions for himself as a way to increase his self-awareness and self-efficacy. He asked managers and leaders to do the same.

- What are my strengths?

- How do I perform?

- What are my values?

- Where do I belong?

- What will I contribute?

- What is my responsibility to those on whom I depend for my contribution?

For now, let’s take a look at how one successful person, Charl, managed himself through to higher performance and personal satisfaction using three of these questions.

What are my strengths?

Drucker’s premise is that our performance relies on our strengths, not our weaknesses. Knowing our strengths puts us in situations where our strengths produce results.

Following Drucker’s approach, when Charl starts new roles or projects – personal and professional – he habitually writes down the results he expects to achieve. At year’s end, he compares his planned to his actual results – the same exercise he uses for his company’s financial performance. He uses the difference between his planned and his actual results as a way of identifying the degree to which he played to his strengths that year.

This year, Charl was pleasantly surprised about how much closer he came in some areas in predicting his results – and how much more satisfied he was feeling along the way. Charl’s success coincided with the strengths he not only played to but deliberately sharpened. He also realized he hadn’t always been clear or honest with himself about the ways he performs best. And how much he was evolving over time.

How do I perform? Under what conditions do I work best?

Charl always took pride in being someone who really produces results. He sets few priorities and challenging goals and focuses. Really focuses.

But this past year he decided to focus on a dream. A creative project that had little monetary value. Just creative impulse. In this year’s annual look-back focusing on this new creative project, he realized he got the results and satisfaction he’d hoped for under three essential but very different conditions: thought partners, accountability partners, and structure.

This year he deliberately sought out broader groups of like-minded creative types. He intentionally stretched himself to do more thinking out loud and listening to others’ dreams and ambitions. Until recently, Charl didn’t think this was something a high-level business driver like himself should depend on. Others might need this, but not him.

This was new. He’d always thought of himself as being a self-starter — independent thinker and consistently self-driven.

Charl realized he got his best results with regular back and forth in a number of regular but very different small groups of people he had come to respect and rely on. In these small groups — meeting globally via Zoom or locally for breakfast or in meetings scheduled ad hoc, he — and they — candidly shared goals, highs, lows and accountabilities. The essential element he realized was “exchange” – they share; he shares. No holds barred. No hierarchy. No status. Regular interaction with thought partners and accountability partners with whom he’ll check in to confirm he’s delivering what he promised himself.

Charl prefers to ultimately work and finish alone. As extroverted as all this “exchanging” sounds, Charl performs best when he writes. Writing down his thoughts or drawing out simple pictures or diagrams not only centers him, writing helps Charl process what’s going on in his busy mind. His timed morning routine provides another structure that feeds his creativity. He knows he learns best when he puts pen to paper, notetaking or writing email “zero drafts” of important correspondence – then editing from the reader’s perspective.

It’s equally important to Charl to have these accountability partners. He can be counted on to meet and exceed his goals.

Now when his interests and passions veer in new and creative directions, he knows he performs best with thought partners and accountability partners. He consistently proves accountable to fellow board members, investors, shareholders. But new percolating ideas needed more: structured exchange with peers, friends, trusted colleagues with whom he can share his ideas, dreams, goals and to whom he is expected to report.

His creativity and desire for personal freedom and choice also depend on structure and accountability. He learned to accept this paradox.

What is my responsibility to those on whom I depend for these results?

The other question Charl feels has made a big difference in his success is the regular reminder this question brings.

For Charl, this means he is responsible for listening and observing how each of the members of his various cohort groups operate best, their strengths, their values. If he doesn’t know, he asks. He knows he has to keep in touch with them, make himself available. It’s one set of relationships among many that he depends on for his success. His honest self-assessment revealed that he wants to earn the trust of this group and others on which he depends.